The sinuses of extinct ocean-dwelling ancestors of modern crocodiles were a major factor in keeping them from becoming into deep dives like whales and dolphins, as an international team of paleobiologists has convincingly shown.

The huge snout sinuses of thalattosuchians, which lived during the dinosaur era, may have prevented them from venturing into the deep, according to a recent study published in Royal Society Open Science.

Over a period of around 10 million years, whales and dolphins (cetaceans) transitioned from land-dwelling mammals to entirely aquatic species.

They produced sinuses and air sacs outside of their skulls throughout this period, and their bone-enclosed sinuses shrank.

This would have prevented pressure spikes during deeper dives, enabling them to descend hundreds of meters for dolphins and thousands of meters for whales without causing skull damage.

There are two primary families of Thalattosuchians, that existed throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous eras.

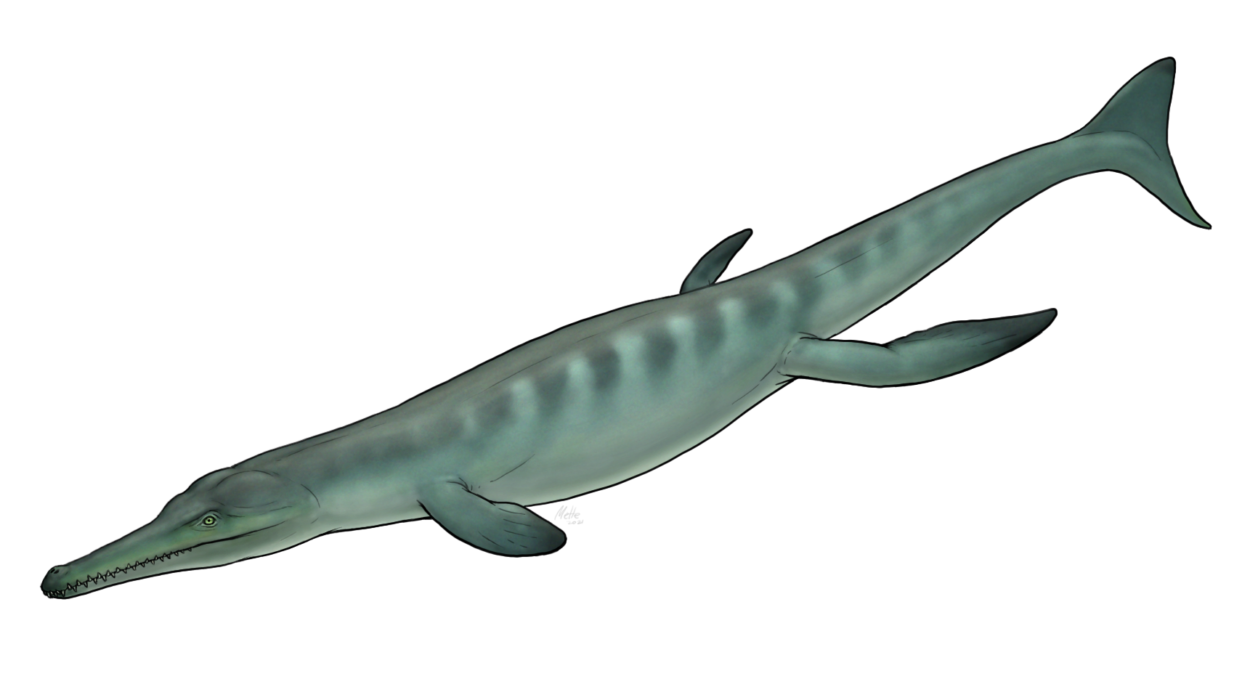

Similar to contemporary gharial crocodiles, Teleosauridae most likely lived in estuaries and coastal waters. With their streamlined body, flipper-like limbs, and tail fins, among other marine adaptations, Metriorhynchidae, on the other hand, were better suited to life at sea.

In their evolutionary transition from land to water, researchers from the University of Southampton, University of Edinburgh, and other institutions sought to determine whether thalattosuchians had developed sinus adaptations comparable to those of whales and dolphins.

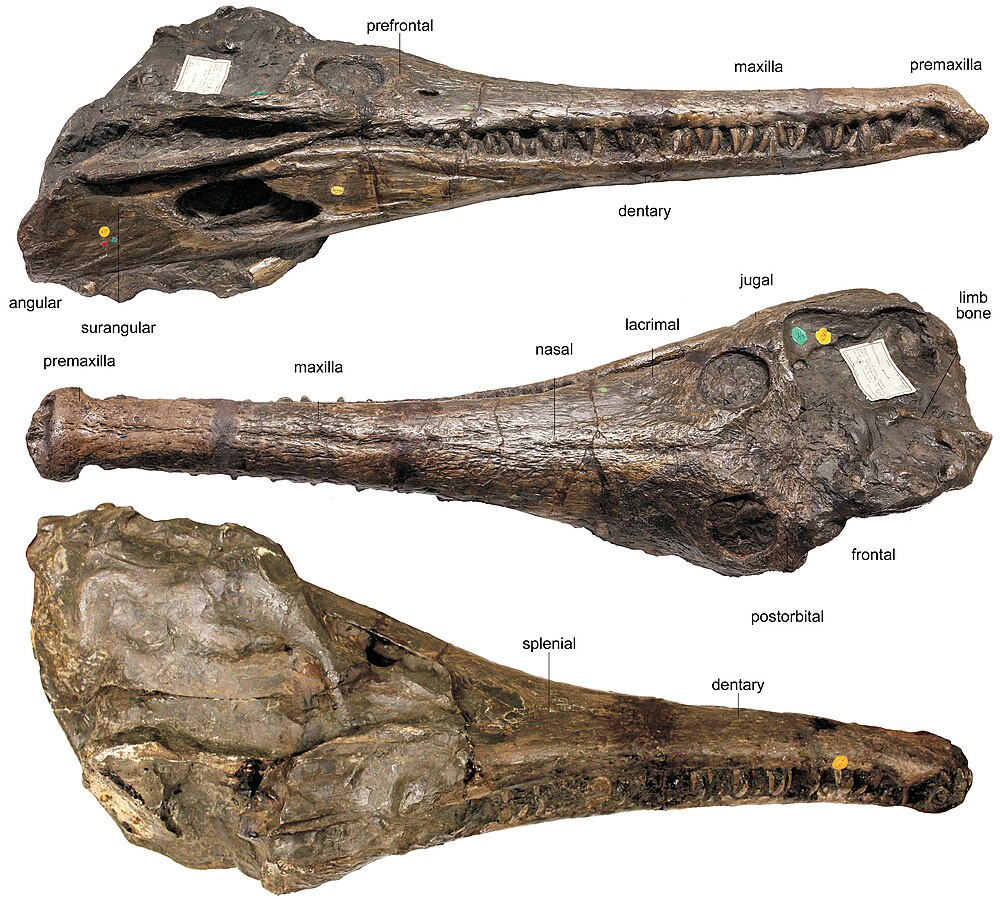

The scientists measured the sinuses of 11 thalattosuchian skulls, 14 contemporary crocodile skulls, and six more fossil species using computed tomography, a specialized type of scan.

As they grew more aquatic, they discovered that, like whales and dolphins, their braincase sinuses shrank throughout thalattosuchian development. The team believes that buoyancy, diving, and feeding factors are probably at blame.

However, the study also discovered that thalattosuchians’ snout sinuses grew larger than those of their progenitors once they were completely aquatic.

According to Dr. Mark Young, the principal author of the study from the University of Southampton, “the regression of braincase sinuses in thalattosuchians mirrors that of cetaceans, diminishing during their semi-aquatic phases and then diminishing further as they became fully aquatic.”

Additionally, extracranial sinuses formed in both groups. However, the wide snout sinus systems of metriorhynchids prevented them from diving deeply, while the sinus system of a cetacean helps regulate pressure around the head during deep dives.

“The air in the sinuses would compress at greater depths, causing discomfort, potential damage, or even collapse of the snout due to its inability to withstand or equalize the rising pressure.”

In contrast to seafaring reptiles and birds, which use salt glands to expel salt from their bodies, whales and dolphins have extremely effective kidneys that filter salt into seawater.

According to the study, metriorhynchids’ bigger, more intricate snout sinuses would have assisted in draining their salt glands, much like those of contemporary marine iguanas.

“Encrustation,” in which the salt hardens and obstructs the salt excreting ducts, is a significant issue for animals with salt glands. While marine iguanas sneeze to push the salt out, modern birds shake their heads to avoid this, according to Dr. Young.

We believe that the metriorhynchids’ enlarged sinuses aided in the removal of extra salt. The jaw muscles of birds, such as metriorhynchids, contract to produce a bellows-like effect within their sinuses, which extend from the snout and pass behind the eye. In metriorhynchids, this action on the sinuses would have squeezed the salt glands in the skull, producing a sneeze-like effect akin to that of contemporary marine iguanas.

The study demonstrates how species anatomy, biology, and evolutionary history drive significant evolutionary shifts.

“It is intriguing to learn how extinct animals, like thalattosuchians, adapted to an oceanic lifestyle in their own special way by exhibiting both similarities and differences to contemporary cetaceans,” says Dr. Julia Schwab, a University of Manchester coauthor on the study.

“We’ll never know for certain if, given more evolutionary time, thalattosuchians could have adapted even further to resemble modern cetaceans or if their need to actively drain salt glands presented an insurmountable obstacle to further aquatic specialization,” Dr. Young concludes, speaking on their extinction during the Early Cretaceous period.

About Thalattosuchians

An extinct genus of reptiles that resembled crocs, the Thalattosuchians existed between 200 and 125 million years ago during the Jurassic and Cretaceous eras.

Even though they are frequently called “marine crocodiles,” these animals were very different from modern crocodiles. With their streamlined bodies, long tails, and even certain characteristics that made them more like contemporary dolphins than crocs, thalattosuchians were extremely suited to living in the water!

The limbs of Thalattosuchians developed into flipper-like structures, which made them ideal for exploring the wide oceans, in contrast to their ancestors who preferred the land.

In order to gain a more nimble, swift swimming body, several species in this group—especially those categorized as metriorhynchids—developed tail fins and shed a large portion of their bone body armor.

They were able to pursue fish and other aquatic creatures because of these anatomical alterations that improved their mobility in marine habitats.

Fish-eating animals with long, narrow snouts packed of sharp teeth and other, more robust-jawed species that probably preyed on bigger prey were both included in the varied group of thalattosuchians.

To demonstrate how specialized they were for their aquatic existence, they possessed salt glands, which are comparable to those seen in certain contemporary reptiles, to aid in the processing of salt from saltwater.

Nevertheless, in the early Cretaceous epoch, Thalattosuchians faced extinction in spite of their remarkable modifications. According to some studies, their fall may have been influenced by changes in the environment, which may have been brought on by climate change and changing habitats.

Their fossil record offers important insights into how life may adapt to radically changing settings, a recurrent topic throughout evolutionary history, even if they are not direct predecessors of modern crocodiles.

The majority of Thalattosuchi fossils have been found in Europe, especially in regions that were formerly warm, shallow waters.

By examining these fossils, paleontologists are able to offer insight on the special characteristics that made it possible for these extinct animals to survive in a setting very different from the seas of today.

Alongside the more well-known ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, Thalattosuchians are a fascinating but little-known chapter in the history of marine reptiles.