Indian History from the Past is Significant for Various Reasons

For a number of reasons, it is crucial to learn ancient Indian history. It explains how, when, and where the oldest cultures in India emerged and how people started engaging in agriculture and stock keeping, which made life more stable and established.

It demonstrates how the indigenous Indians of long ago found, made use of, and developed the means of sustaining themselves. We learn how the early people established farming, spinning, weaving, metallurgy, and other occupations, cleared woods, built villages, cities, and finally vast kingdoms.

We also get an understanding of how they arranged for food, housing, and transportation. In order to be deemed civilized, a person must be able to write.

The majority of current writing styles used in India are descended from ancient scripts. Our current languages have historical roots and have evolved over time.

Diverse but Unified

Because so many different ethnicities and tribes coexisted in early India, ancient Indian history is fascinating. Pre-Aryans, Indo-Aryans, Greeks, Scythians, Hunas, Turks, or other peoples called India home.

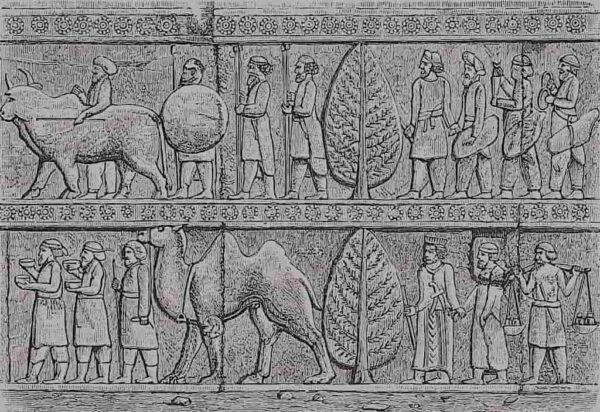

The entire society, art and architecture, language, and literature of India were all influenced by the many ethnic groups to varying degrees. It is now possible to distinguish all of these peoples and their distinctive cultural characteristics from one another.

The blending of cultural aspects from the north and south as well as the east and west is a striking aspect of ancient Indian civilization.

The pre-Aryan aspects are compared to the Dravidian and Tamil cultures of the south, while the Aryan elements are associated with the Vedic and Puranic civilizations of the north.

However, the Vedic manuscripts, which are dated between 1500 and 500 BC, contain several Munda, Dravidian, and other non-Sanskritic terminology.

They represent concepts, organisations, things, and towns related to peninsular and non-Vedic India. Similar to this, numerous Pali and Sanskrit names that denote concepts and organisations that originated in the Gangetic plains may be found in the earliest Tamil manuscripts, known as the Sangam literature, which generally covers the time period between 300 BC and AD 600.

The Application of History to the Present

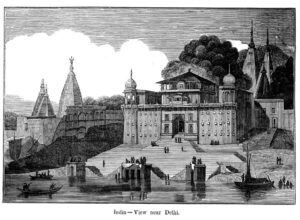

When viewed in light of the issues we currently have, the study of India’s past takes on a special significance. Many individuals are sentimentally moved by what they perceive to be India’s former grandeur, and some call for the revival of ancient culture and civilisation.

Concern for the preservation of historic art and architecture is distinct from this. They sincerely want the previous social and cultural norms to return. A precise and correct grasp of the past is necessary for this.

There is no denying that ancient Indians achieved outstanding progress in a number of different sectors, but their accomplishments cannot compare to what contemporary technology and science have accomplished.

We cannot deny the egregious social injustice that characterised ancient Indian culture. The poorer classes, especially the Shudras and untouchables, were burdened with ailments that shock our modern sensibilities.

Law and tradition also discriminate against women and favour men. All these injustices would inevitably be revived and strengthened by the return to the previous way of life.

The ability of the ancients to overcome challenges brought on by both natural and human forces can inspire hope and confidence in the future, but any attempt to bring the past back will only serve to perpetuate the social injustice that blighted India. Due to all of this, it is crucial that we comprehend the significance of the past.

Colonialist Opinions and their Impact

Recent studies into the heritage of ancient India did not start until the second half of the eighteenth century in order to meet the demands of the British colonial administration, even though educated Indians still preserved their dealing with similar the version of handwritten epics, Puranas, and semi-biographical works.

They had trouble enforcing the Hindu inheritance rules when Bengal and Bihar came under the control of the East India Company in 1765.

This led to the famous Manu Smriti (the law book of Manu) being translated into English as A Code of Gentoo Laws in 1776. To manage Hindu civil law and upon doing to administer Muslim civil law, British judges partnered with pandits.

The Asiatic League of Bengal was founded in Calcutta in 1784, marking the culmination of the first attempts to study ancient laws and practises, which lasted for the most part up until the 18th century.

Nationalist Strategy and its Effect

To Indian intellectuals, especially those who had acquired a Western education, all of this naturally presented a significant difficulty.

The colonialist revisions of their past were upsetting to them, in addition, at that time, they were troubled by the contrast between the developing capitalist society in Britain and India’s deteriorating feudal society.

A group of academics set out on a quest to improve Indian society as well as to rewrite the history of the indigenous peoples of the past to support social reforms and, more crucially, self-government.

There were many historians who took an impartial and rationalist stance, but the majority of them were influenced by the nationalist ideals of Hindu revivalism.

Rajendra Lal Mitra (1822–91), who created a book named Indo-Aryans and disseminated some Vedic texts, falls into the second type. He developed a persuasive tract to demonstrate that early people times consumed beef. He was a great admirer of ancient heritage and took a logical view of the old culture.

Others attempted to demonstrate that the social stratification was essentially identical to either the class structure based on the division of labour prevalent in also before the ancient communities in Europe, despite its uniqueness.

Moving away from Political History

Sanskrit-trained British historian A.L. Basham (1914–1986) questioned the appropriateness of approaching ancient India from a contemporary perspective. His previous publications demonstrate his intense interest in some heterodox sects’ materialist philosophy.

Later, he came to believe that reading about the past was a fun and interesting activity. The Wonder That Was India, published in 1951, is a sympathetic examination of the numerous facets of ancient Indian culture and civilization free from the preconceptions that mar the writings of V.A. Smith and many other British authors.

A significant transition from social to semi-history is made in Basham’s novel. An Approach to that same Analysis of Indian History (1957), written by D.D. Kosambi (1907–1966) and later made popular in The Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline, shows a similar change (1965).

In Indian history, Kosambi forged a new path. His approach is based on a materialist reading of history that comes from Karl Marx’s works.

He argues that the evolution of the elements and production connections is inextricably linked to the background of ancient Indian society, economics, and culture.

The stages of social and economic evolution in terms of tribe and class dynamics were first illustrated in his survey volume. He received criticism from a number of academics, especially Basham, but his book is still widely read today.

Communal Method

Since 1980, certain writers from India and the World have approached the research of ancient India in a confrontational and illogical manner.

They link Hinduism to it. Colonialist historians under British rule purposefully minimised India’s accomplishments and credited significant facets of Indian culture with foreign influence. Indian historians emphasised India’s cultural contribution to the world.

As a result, nationalism and colonization continued to clash in historical interpretation. The circumstance has changed now. On one side, there is radical egalitarianism and irrationalism, while on the other, there is rationalism and professionalism.

The Indo-Aryans are today regarded as native Indians by those who earlier ascribed the Polished Grey Ceramic to the Vedic civilization and searched for it outside of India.

They contend that external Muslims and Christians are outsiders. Such generalisations must be logically read from the sources and objectively analysed.

In terms of religion, both Hinduism nor the Hindu worldview are mentioned in any old Sanskrit texts or other old sources. Hinduism and Hindutva are constantly brought up by communal writers.

Given the situation, historians who adhere to objective, medical methods must exercise caution and abide by logic and widely accepted historical norms.