Coins:

While a substantial number of coins and inscriptions have been discovered on the surface, exploration has uncovered all of them. Numismatics is called the study of coins. And so is the case today, the ancient Indian currency was not distributed as paper but as metal coins. Coin castings made from burnt clay have been found in huge amounts. Most of them refer to the Kushan period, that would be to say, the first three centuries of Christianity. The use of such molding practically vanished in the post-Gupta period.

Since there was nothing like the current financial system in ancient times, people held money in porcelain and even in brass pots, and kept it as valuable hoards from which they could fall back in case of need.

In various parts of India, several of these hoards have been found, containing not only Indian coins but also those minted abroad, such as in the Roman empire.

As Britain has ruled over India for a long time, British authorities have persisted in transferring much of the Indian coins to private and public reserves in Britain.

We have catalogs of coins at the Calcutta Indian Museum, Indian coins at the London British Museum, and so on. A significant number of coins have yet to be cataloged and issued.

Our initial coins depict a few symbols, but later coins represent the portraits of kings and gods, as well as their names and dates. The places where they are located reflect the field in which they exist.

These have helped us to recreate the heritage of many ruling dynasties, especially the Indo-Greeks who, in the second and first centuries BC, migrated from northern Afghanistan to India and ruled here.

Since coins have been used for various reasons, such as presents, a means of payment, and a mode of trade, economic history is given tremendous light. With the approval of the kings, several coins were produced by guild members of merchants and goldsmiths.

It demonstrates that crafts and trade have become significant. On a broad scale, coins facilitated exchanges and led to commerce.

The post-Maurya period presents a significant number of Indian coins. They were made of lead, pot, copper, bronze, gold, and silver. The greatest number of gold coins were issued by the Guptas.

All this suggests that trade and exchange, particularly in the post-Maurya period and a good part of the Gupta period, flourished. Just a few coins belonging to the post-Gupta period, however, have been discovered, suggesting a drop in trade and trade during that period.

Coins also represent kings and gods and have divine icons and stories, both of which shed light on the period’s art and faith. While their bargaining power was poor, cows were often used as coins. In post-Gupta periods, they appear in large statistics but may have been used earlier.

Inscriptions:

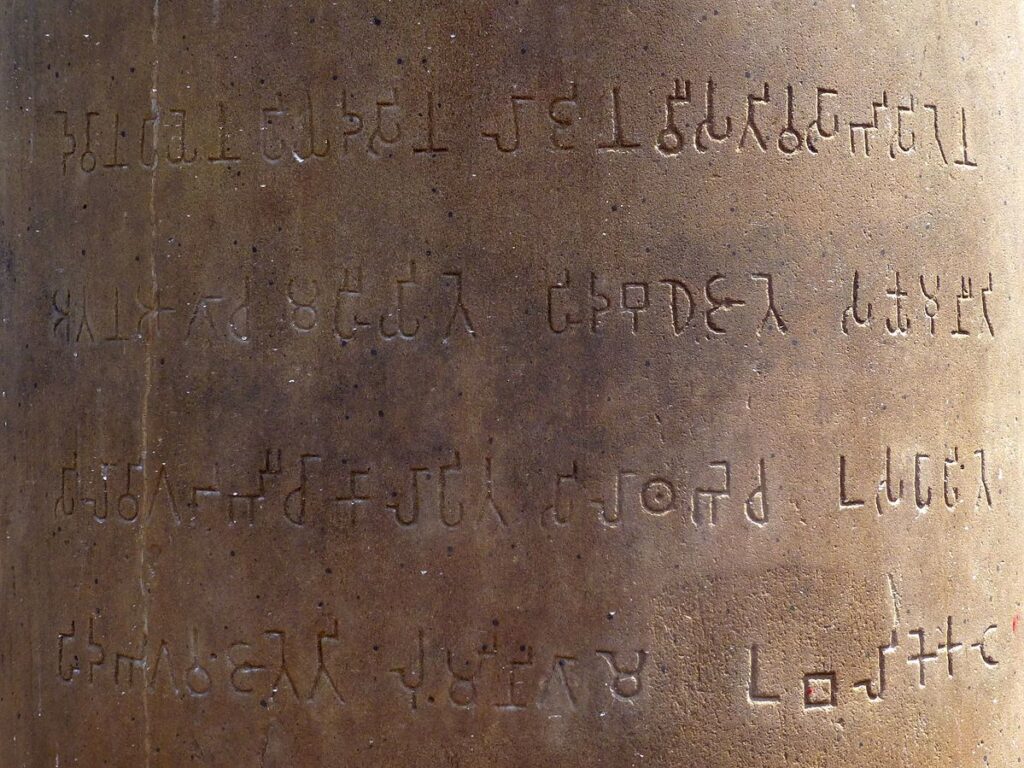

Carvings are much more crucial than coins. Their analysis is called epigraphy, and paleography is the study of ancient writing used in inscriptions and other old documents. Seals, stone blocks, rocks, copperplates, temple walls, wooden tablets, and bricks or pictures were decorated with inscriptions.

The earliest inscriptions have been documented on a stone in India as a whole. Copperplate, however, started to be used for this purpose in the early centuries of the Christian period. The tradition of engraving inscriptions on stone persisted in South India on a wide scale even then.

We also have a significant number of inscriptions documented on the walls of temples in that area to act as permanent documents.

Inscriptions are held in different museums in the region, like coins, but the greatest number can be found in the office of the chief epigraphist in Mysore. In the third century BC, in Prakrit, the earliest inscriptions were written.

In the second century AD, Sanskrit was introduced as an epigraphic medium and its use in the fourth and fifth centuries became popular, but Prakrit continued to be used even then. In the ninth and tenth centuries, inscriptions continued to be written in regional languages.

Except for the north-western part, the Brahmi script prevailed practically throughout India. In writing Ashokan inscriptions in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Greek and Aramaic scripts were used, but Brahmi remained the dominant script until the end of the Gupta period.

If he has mastered Brahmi and its variants, an epigraphist will decode most Indian inscriptions up to around the seventh century, but then, in this language, we find strong regional variations.

Some scholars regard inscriptions found on the seals of Harappa belonging to around 2500 BC as symbolic. The oldest deciphered inscriptions in the history of India are Iranian.

They are found in Iran and belong to the sixth-fifth century BC. In the cuneiform script, they appear in Old-Lndo-Iranian and also in Semitic languages. They talk of the Hindu or Sindhu area’s Iranian conquest. The oldest deciphered ones are, of course, Ashokan inscriptions in India.

They are usually written in the third century BC in the Brahmi script and Prakrit language. They shed light on the history of Maurya and the contributions of Ashoka.

Firoz Shah Tughlaq discovered two Ashokan pillar inscriptions in the fourteenth century, one in Meerut and another in a location called Topra in Haryana. He took them to Delhi and asked his empire’s pandits to decode the inscriptions, but they were unable to do so.

The British encountered the same challenge when they found Ashokan inscriptions in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. James Prinsep, a civil servant working for the East India Company in Bengal, first deciphered these epigraphs in 1837.

We do have different forms of inscriptions. Some transmit royal orders and decisions to officials and the people in general concerning social, religious, and administrative matters. In this group, Ashokan inscriptions belong. Some are votive accounts of Buddhism’s adherents, Jainism, Vaishnavism, Shaivism, etc.

They appear as signs of devotion on pillars, tablets, temples, or pictures. Yet other forms praise the characteristics and accomplishments of kings and conquerors and ignore their defeats or weaknesses. The Allahabad Pillar inscription of Samudragupta belongs to this group.

Finally, we have a lot of donation records which refer in particular to gifts of money, livestock, land, etc., mainly for religious purposes, made not only by kings and princes but also by craftsmen and merchants.

For the study of the land system and administration in ancient India, inscriptions documenting land grants, made principally by chiefs and princes, are very significant. These were engraved mainly on copperplates.

They document grants made to monks, priests, churches, monasteries, vassals, and officials for land, taxes, and villages. They have been written in all languages, including Prakrit, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu.