Literary Sources:

Although the ancient Indians learned how to write as early as 2500 BC, our earliest writings date from the fourth century AD and are situated in Central Asia.

It was written on birch bark and palm leaves in India, but it was also written on sheep leather and wooden tablets in Central Asia, where the Prakrit language had spread out of India.

These texts are called inscriptions, but they are almost as effective as books. Manuscripts were very highly regarded while printing was not understood. While old Sanskrit manuscripts are found throughout India, they mostly refer to southern India, Kashmir, and Nepal. Inscriptions are now mostly kept in museums and manuscripts are kept in libraries.

The bulk of ancient books have theological themes. The Vedas, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the Puranas, and other Hindu holy texts are examples. They shed a lot of light on ancient social and cultural circumstances, but it’s difficult to put them in the right time and place.

The Rig Veda can be dated to c. 1500-1000 BC, while collections such as the Atharva Veda, the Yajur Veda, the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas, and the Upanishads date from around 1000-500 BC. Almost every Vedic text includes interpolations, which usually occur at the beginning of the end and occasionally in the middle.

The Rig Veda is largely a set of prayers, while later Vedic texts contain prayers as well as rites, sorcery, and mythological tales. The Upanishads, on the other hand, contain metaphysical speculations.

To comprehend the Vedic scriptures, it was appropriate to research the Vedangas of the Veda limbs. These Veda supplements included phonetics (Shiksha), rituals (Kalpa), grammar (vyakarana), etymology (nirukta), metrics (Chanda), and astronomy (Jyotisha), and a great deal of literature developed around each of these topics. They were published in the style of prose precepts.

Because of its brevity, a precept was considered a sutra. The grammar of Panini, written about 450 BC, is the most prominent example of this writing. Panini illuminates the laws of grammar while also offering insight into the society, economy, and history of his day.

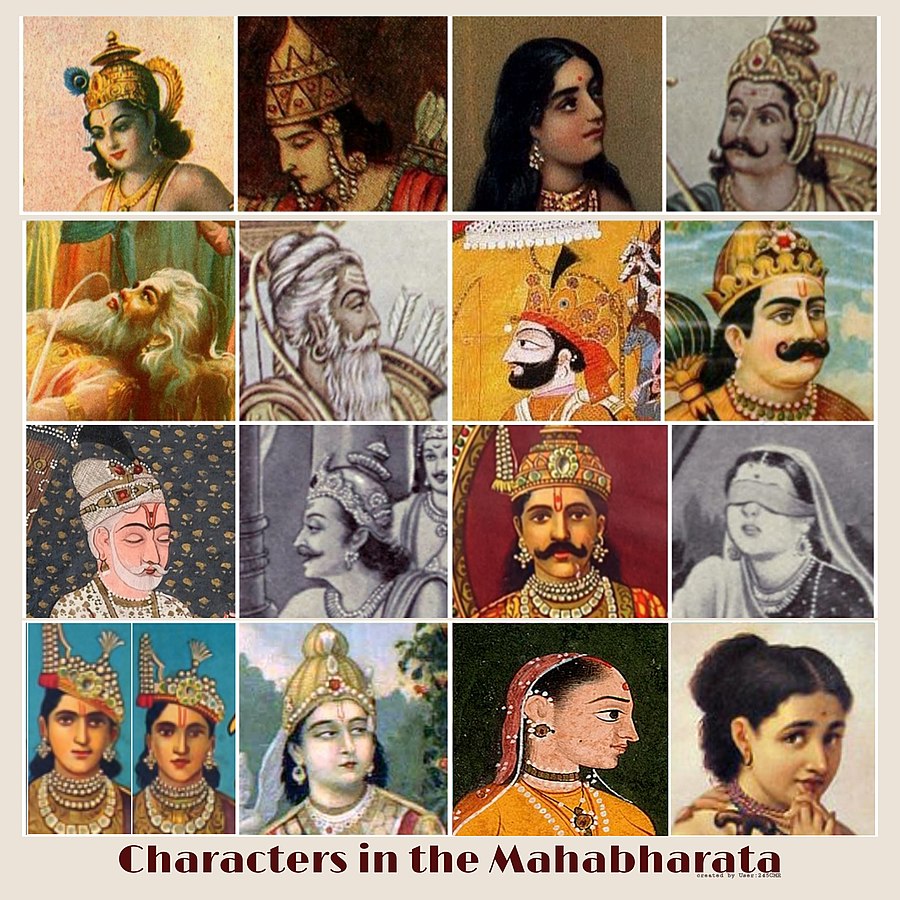

Around AD 400, the two epics and the major Puranas seem to have been compiled. The Mahabharata, attributed to Vyasa, is the oldest of the epics and most likely portrays events from the 10th century BC to the 4th century AD. Originally, it consisted of 8800 verses, called Jaya, or a set concerned with a victory.

These were expanded to 24,000 people and dubbed Bharata because they included stories about the descendants of Bharata, one of the first Vedic tribes.The Mahabharata, also known as the Shatasahasri Samhita, is the culmination of the final collection, which raised the number of verses to 100,000. It is made up of narration, informative, and didactic material.

The key narrative relating to the Kaurava-Pandava dispute refers to the later Vedic period, the descriptive portion of the post-Vedic period, and the didactic portion usually relate to the post-Maurya and Gupta periods. Similarly, the Ramayana of Valmiki initially consisted of 6,000 chapters, which grew to 12,000 and finally to 24,000.

Although it seems to be more cohesive than the Mahabharata, it includes didactic aspects that were later incorporated.

In the fifth century BC, the Ramayana was being written. Following that, it went through five phases, the most recent of which seems to have arisen in the twelfth century AD. The text seems to be older than the Mahabharata in general.

We have a wide corpus of ritual literature from the post-Vedic period. The Shrautasutras, which detail several ostentatious royal coronation ceremonies for princes and men of a substance belonging to the three higher varnas, outline grand public sacrifices to be made by princes and men of a substance belonging to the three higher varnas.

Similarly, domestic ceremonies related to birth, naming, holy thread investiture, marriage, funerals, etc. are prescribed in the Grihyasutras. Both the Shrautasutras and the Grihyasutras concern c. 600-300 BC. The Sulvasutras, which recommend different types of measurements for the building of sacrificial altars, are also worth noting.

The Jaina and Buddhist holy books make references to historical figures and events. Pali, which was spoken in Magadha or South Bihar and was a kind of Prakrit, was used to write the earliest Buddhist texts. They were eventually collected in Sri Lanka in the first century BC, but the canonical portions represent the state of affairs in India during the Buddha’s lifetime.

They tell us about the Buddha’s life as well as some of his royal contemporaries who ruled over Magadha, north Bihar, and eastern Uttar Pradesh. The tales of Gautama Buddha’s previous births provide the most significant and fascinating component of non-canonical literature.

It was assumed that the Buddha had over 550 births before being born as Gautama, all of which were in the shape of animals. Every birth story is known as a Jataka, or folk tale. The Jatakas offer unique insight into the social and economic circumstances of the fifth and second centuries BC.

They often make passing references to political activities during the Buddha’s time. The Jaina texts were written in Prakrit and collected in Valabhi, Gujarat, in the sixth century. They do, however, contain a variety of passages that assist in reconstructing the political past of eastern UP and Bihar during Mahavira’s reign. Traders and exchanges are mentioned many times in the Jaina texts.

There is also a significant body of secular literature. This group comprises the Dharmasutras and Smritis, as well as their commentaries, which are referred to as Dharmashastras. The Dharmasutras were written between 500 and 200 BC, and the key Smritis were written within the first six centuries of the Christian period.

They describe the roles of the various varnas, as well as kings and their administrators. They spell out the rules for marriage as well as the laws regulating the possession, selling, and inheritance of land. They also stipulate fines for robbery, assault, murder, adultery, and other crimes.

The Arthashastra of Kautilya is a significant law text. The text is divided into fifteen books, with Books II and III dating from an earlier time and seeming to have been composed by separate hands. Although this text was completed at the beginning of the Christian period, its earliest parts represent the state of civilization and economy during the Mauryas’ reign.

It includes a wealth of knowledge on ancient Indian politics and economics.

Grammatical works are critical for historical restoration among non-religious sources. Panini’s Astadhyayi is the first of them. Panini was a native of the subcontinent’s northwestern region. In the Pali texts, which primarily depict Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, he is not mentioned. V.S. Agrawala, who has written in both Hindi and English about Panini’s India, dates Panini to about 450BC. Panini’s text, he argues, contains the most details about pre-Mauryan janapadas or tribal states. Patanjali’s 150 BC commentary on Panini provides crucial details about post-Maurya times.

We also have Bhasa’s, Sudraka’s, Kalidasa’s, and Banabhatta’s works. They represent the realities of the periods in which the authors existed, in addition to their literary merit. Kalidasa’s works contain kavyas and dramas, the most well-known of which is Abhijnanashakuntalam. They are not only brilliant artistic compositions, but they also give us glimpses into the Guptas’ social and cultural lives.

We also have one of the oldest Tamil texts in the catalog of Sangam literature, in addition to Sanskrit references. Poets who gathered in colleges patronized by chiefs and kings produced this literature over a three to four-century period. These colleges were called Sangam, and the literature created in these assemblies was known as Sangam literature.

The corpus collection is dated to the first four centuries of Christianity, though it was probably finished by the sixth century.

Sangam poetry is grouped into eight anthologies called Ettuttokai and includes around 30,000 lines of poetry. Poems are compiled in large communities, such as Purananuru (The Four Hundred of the Exterior). Patinenkil Kannakku (The Eighteen Lower Collections) and Pattuppattu are the two major classes (The Ten Songs).

Since the former is commonly believed to be older than the latter, it is regarded as historically important. The Sangam texts have multiple layers, which can currently be classified based on style and content but can also be identified based on stages of social evolution, as will be seen later.

The Sangam texts, especially the Rig Veda, differ from the Vedic texts. They do not fall into the heading of religious literature. The short & long poems were written in honor of numerous heroes and heroines by several poets and are thus secular. They are not easy albums, but high-quality literature.

Many poets refer to a hero, a chief, or a king by name and depict his military exploits in great detail.

He is praised for the gifts he provided to bards and warriors. These poems were likely recited in the trials. They are related to Homeric heroic poetry because they reflect a heroic age with warriors and wars.

These documents are difficult to use for historical purposes. The proper names, titles, dynasties, kingdoms, battles, and other events mentioned in the poems may be partially accurate. Inscriptions from the first and second centuries indicate some of the Chera kings listed in the Sangam texts as donors.

Many settlements are mentioned in the Sangam texts, including Kaveripattanam, whose thriving presence has now been archaeologically established. They also note the Yavanas landing with their ships, buying pepper with gold, and supplying the natives with wine and women slaves.

This trade is recorded not only in Latin and Greek literature but also in archaeological discoveries. The Sangam literature is a significant source of knowledge about the social, economic, and political lives of people living in deltaic Tamil Nadu in the early Christian centuries. Foreign accounts and archaeological discoveries back up what it means about trade and commerce.