The Land’s Historical Relationship Between a Single Empire’s North and South Parts

Our main interest is with the region south of the Vindhyas, a rough, hilly area that nearly runs east to west anywhere along the Tropic of Cancer and varies greatly in width and elevation.

Mostly on the southern side of both the Vindhyas, but even so, it is a dramatic fall again from crest to such Narmada valley, along with a hillside wall substantiated by several forest-clad spurs encompassing the deep, slender through while of the river that is bordered on the south by the Satpura-Mahadeo-Maikal range.

Just on the northwest part of the Vindhyas, this same slope is soft and there aren’t any signposted spurs or The Tapti travels straight to the Narmada to the western and the Mahanadi to the Bay of Bengal on the east from the southern slopes of both the Efficient and effective.

Although this double wall essentially separates the plains of North India from the peninsular South, it does not significantly impede communication between the two areas.

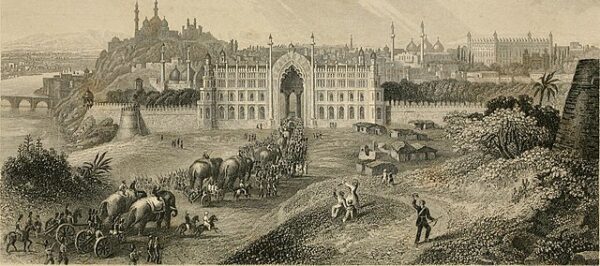

There has never been a time when the two regions did not interact politically and culturally, and at least three times before the arrival of British control, the North and the South were both components of a single empire that encompassed almost all of India.

Ocean Between the Arabian Sea and Other

Seen between the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, the peninsula projects into the Indian Ocean and lessens to a terminus at Cape Comorin. The Malabar and Coromandel coasts both reach a distance of 1,000 miles from Cape Comorin, with the former extending to the northwest and the latter to the northeast.

Since neither coast has many excellent natural harbours, the west coast does mildly stronger than the Coromandel coast in this regard since cities like Cochin, Goa, and Bombay provide reasonably secure anchorages for ships.

Peninsular India established and maintained a fairly brisk marine trade with the countries on either side and played a significant role in the colonization of the eastern regions across the Bay of Bengal due to its location halfway along the maritime routes from the Mediterranean and Africa to China. And some of its kings, including the Satavahanas, Pallavas, and Cholas, are known to have given special attention to the upkeep of a potent navy.

Although the sailors of the Chola nation grew to be regarded as leaders in shipping difficulties in the Indian Ocean and were mentioned by the Arab cartographers of the Middle Ages, the Malabar coast had a deplorable reputation for the piratical activity of its sailors for several centuries.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea contains a historical overview of the ports on the Indian subcontinent and the circumstances surrounding maritime trade.

A Triangular Block forms the Peninsula’s Core

The peninsula’s core is a hexagonal block of incredibly old rocks that spans the majority of its length from the Satmala-Ajanta hills to the Nilgiris. This has a typical plateau relief: its surface slopes gently down to a lower border in the east, the Eastern Ghats, which is created by a thin strip of rough, wet lowland on its western side and overlooks the west coast.

A belt of grassland known as the Carnatic lies in between the Eastern Ghats or the Corinthian coast and is far larger, smoother, and more arid than the western strip.

The Western Ghats, which frequently rise in levels from the coast and are visible from the west, provide the impression of a massive sea wall, hence the term “ghats.” The Nilgiris with Dodabetta at such a position of 8,760 feet, in which the Eastern Ghats meet the Western, is a steep and rocky range of hills that begin at a touch over than 2,000 inches above sea level in the north but rise to far more than 4,000 feet at approximately the latitudes of Mumbai.

The Palghat or Coimbatore gap, which is located southeast of the Nilgiri plateau and spans a distance of about 20th miles from north to south, serves as a gateway to lowland areas from the Deccan to the Malabar coast at a height of roughly a million feet above the sea level.

Deep Valleys Characterized by Magnificent Scenery

The Anaimalai hills are the most remarkable range in South India; the greater menu includes a succession of plateaux at a height of 7,000 feet that rise to peaks over 8,000 feet.

They are separated between them by river valleys with breathtaking beauty and surrounded by tumbling downs and dense evergreen trees.

At a height of 3 to 4,000 feet typically, the method for reducing to the west currently contains coffee growing on thousands of acres. In addition to producing the majority of the timber typical of temperate forest belts within the same altitude, it is home to the teak belt and many valuable game species, including the elephants after whom the range is named. The Käan, Muduvan, and Pulaiyan are among the hill tribes that call it home.

Little of the grandeur achieved by the uniform structure but erratic outlines of the western ghats may be seen in the Eastern Ghats.

Despite being dispersed, fragmented, and much lower in elevation, they appear to be geologically far older than the Western Ghats. Starting in Orissa, they travel south as far as latitude 16°N before entering Andhra state while remaining parallel to the shore.

In order to create the southern boundary of the Deccan plateau in its largest context and to intersect the Western Ghats in the Nilgiris, they first retreat from the coast and travel in a north to south direction until they reach the equator of Madras.

Great Rivers of the Plateau

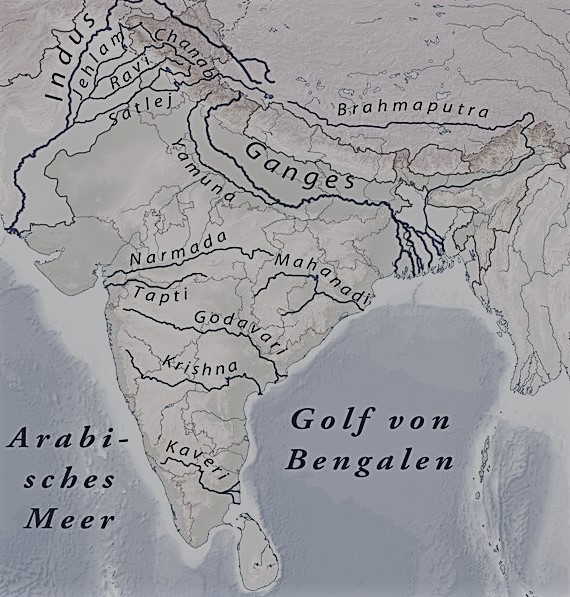

The Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri are the three principal rivers of the plateau; the Mahanadi may be included in this list. The Penner, Palar, Pennar, Vaigai, and Tambraparni are significant minor rivers. These rivers flow quickly through deep, rocky valleys at the beginning of their courses, giving the impression that they would somewhat discharge the country than find fresh it.

However, as they near the coastal plain, where the terrain is more level, dams have really been built across all of them, diverting their waterways for agriculture. Wide swaths of irrigated crops are present in the Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri deltas.

Only each Ganges and the Indus are superior to the Godavari in India in terms of their sacredness, the beauty of their route, and their usefulness to humans.

It begins in the hills beyond Trimbak in the Nasik district, only 50 miles from the Arabian Sea, and travels 900 miles till striking the Bay of Bengal, draining a region of 1,12,000 square miles. While it flows across a constrained rocky bed beyond Nasik, the banks further east are shallower and thus more earthy.

The Piranha, which joins Sironcha as below carries the united Wardha & Wainganga rivers that drain the entire Satpura and Nagpur plains and is linked on its left.

A few meters higher down, it is accessed by the Indravati, which empties the untamed and wooded Eastern Ghats regions of Bastar and its neighbours. As the river flows into the ocean below this junction, it travels primarily in the southeast.

Tungabhadra’s Historic Natural Frontier

Through the ages, the Tungabhadra also worked as a historical natural border between the Chalukyas of Bdmi, the Rashtrakutas, and the Chalukyas of Kalyani from its north, and even the Pallavas and Cholas to its south, not to mention the Gangas who were largely ruled by one of those kingdoms or another. made numerous attempts to expand their influence across the river but they only achieved mediocre success.

Upon that southern bank of the Tungabhadra, the ancient cities of Vijayanagar and Kampili rose. And even the Raichur doab, which lies between the Krishna and the Tungabhadra, could very easily be referred to as the Deccan’s cockpit.

The Kaveri also referred to as the southern Ganges, flows 475 kilometers and is renowned for its holiness, beautiful landscape, and usefulness for agriculture. Tamil literature is full of sentiments of pious and sincere adoration for the life-giving qualities of its water, and it cherishes many traditions from its ancestors.

It originates in the Brahmagiri, close to Talakaveri in Coorg, and flows primarily in a south-easterly direction across the plateau, creating large falls as it descends the Eastern Ghats, before passing through the Carnatic plain past Trichinopoly and Tanjore to the Bay, which it enters via a number of tributary rivers in the Tanjore district.

After taking a winding route through Coorg through a rocky bed surrounded by steep banks covered in lush flora, it enters the state of Mysore and travels through a small ravine with a tumble of 60 to 80 feet in the Chunchankatte rapids before widening.