Under the strong, but unpopular, Nandas dynasty in the 4th century B.C., the empire of Magadha experienced a significant expansion.

Puranic sources claim that the Nandas overthrew all competing kings and established themselves as the only rulers of all of India. It is difficult to say how far their influence reached the South.

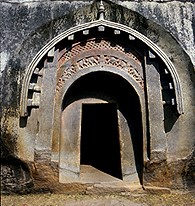

The well-known Hathigumpha inscription of Kalinga’s ruler in the 2nd century B.C., Kharavela, seems to prove that it comprised Kalinga.

The inscription on this stone alleges that King Nanda captured a Jina temple and other artifacts from the Kalinga dynasty as war booty and names a Nanda raja in relation to the construction of a sprinkler system. Although there is little evidence to support this tradition, Kannada manuscripts from Mysore from the 10th and 11th centuries A.D. preserve hazy memories of the Nandas’ rule in the Kuntala country.

Nader, on the upper reaches of the Godavari, has occasionally been interpreted as the persistence of an ancient name like Nau-Nandadhera and as a sign of the limited extend of Nanda’s power in the Deccan.

Strike Puräna coins, which are widespread in the Deccan, South India, and Ceylon in addition to North India, are undeniable proof of early interactions between the North and South whose specifics have since been lost. However, while they allow us to surmise the occurrence of trade connections, they are useless for determining the southern limit of the Nanda empire.

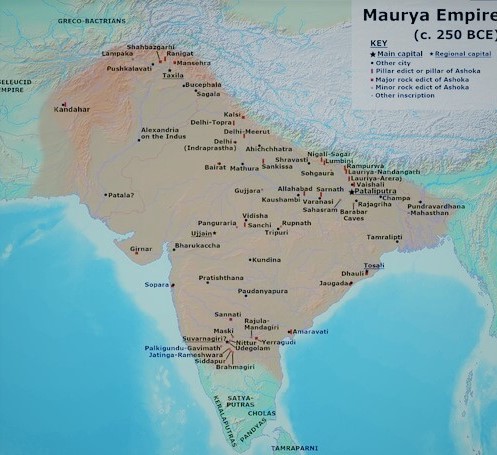

Limits of the Mauryan Empire under Asoka

The incorporation of Kuntala in that empire is consistent with the boundaries of the Asoka-era Mauryan empire as established by the presence of his inscriptions in the South, and there is no conclusive proof that the Mauryan emperors engaged in campaigns of conquering in the South.

The Kannada writings previously described may, in fact, have preserved a true narrative that the Mauryas acquired their Southern lands as a matter of course by destroying the Nanas imperial dynasty. The vast wealth amassed by the Nandas has been well acknowledged and became a proverb among the traditional Tamils.

According to legend, the emperor spent a significant amount of time as a Jain monk in Sravana Belgola in Mysore before later committing himself through sallekhana, or hunger, and outliving his instructor by twelve years. Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Munindra are mentioned in legends from Sravana Belgola and the surrounding area; one of these, which may date back to A.D. 600, discusses the couple (yugma) and claims that theirs was the safe faith (dharma); another, which is even older and undoubtedly not eventually than the 5th-century BC, contains all the details of the above-mentioned tale.

An Acharya who knew he had only a little time to live, sent out the entire religious order away and underwent devotion just with one disciple caring for him as they reached a summit named Katavapra (that is, Chandragiri) in a populous and rich kingdom (Mysore). The lower hill Chandragiri in Belgola is described as having footprints left by both Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta munipati on its summit in two writings again from the Seringapatam neighborhood that date to around the year 900.

Maurya lends some plausibility to this legend

This legend is repeated with some adjustments in later markings at Sravana Belgola with dates from the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Similar evidence is also provided by literary sources, the earliest of which appears to be Harishena’s Brihatkathakola (A.D. 931). This mythology is unlikely in and of itself, and the existence of the Chandragupta muni of the monuments is far from certain despite the lack of any conclusive evidence on the actual death of Chandragupta Maurya.

A few important facts about communication between the North and the South during the early Mauryan empire are revealed in the Arthafastra of Kautilya. According to Kautilya, my teacher believes that the trip to the Himalayas is superior to the way to Dakshinapatha since it is home to valuable commodities including elephants, horses, spices, ivory, skins, silver, and gold. He goes on to explain his own, very different views as follows: Kautilya responds, “No.

The Dakshinapatha is short on woolen fabric, hides, and horses but rich in conch shells, diamonds and other sorts of valuable stones, pearls, and gold objects. The southern trade route via Dakshinapatha, which is frequently used by traders and convenient to travel by, also passes through an area rich in mines and precious goods. The extensive commerce opening up with the South that the establishment of the Nanda and Mauryan empires brought about is practically brought before our eyes in this section.

Kautilya includes varieties of pearls

Due to changing circumstances, Kautilya’s teacher’s (acharya) point of view was quickly losing relevance, and the student asserts that the South was wealthier and more open to commerce in his day than it had ever been. The inclusion of gold, diamonds, and other precious stones and pearls, as well as the convenient travel circumstances along the heavily used routes, need special attention.

It has already been noted that the legendary tale provided by Megasthenes of Pandaia, a daughter of Herakles, ruling the Pandyan empire, must be interpreted as recalling the country’s foundation rather than portraying current circumstances. According to Megasthenes, each day one village paid its proper tribute to the royal treasury. This tribute may have been a payment in kind intended to guarantee a steady supply of food for the royal household’s daily usage.

In his 2nd and 12th rock-edicts, Asoka makes reference to the kingdoms of South India as well as Ceylon. The names of the Chola, Pandya, Satiyaputa, Keralaputa, and Tambapanni are included in the second edict’s more comprehensive list (Ceylon).

All of these regions are categorically stated to have existed outside of Asoka’s empire, but the great empire struck up such cordial relations with them that he attempted to make arrangements for the proper medical treatment of people and animals in each region as well as for the export and planting of helpful herbals and roots wherever they lived required.

It is difficult to pinpoint the Satiyaputa kingdom, and the matter has previously been up for debate. The only tribe fitting this definition known to early Tamil literature is managed to hold to be the Kösar, applauded for their unwavering truthfulness to the plighted word in addition to their heroism in battle.

The name was, until recently, recognized as a tribal name that may be Sanskritized into Satyaputras, “members of the brotherhood of truth.” In the early centuries of the Christian era, they are supposed to have conquered the Tulu nation on the west coast from their home in the Kongu area, which is roughly equivalent to the modern-day regions of Salem and Coimbatore.

The conquest of Kalinga by Asoka

One of Asoka’s most well-known acts, the invasion of Kalinga (about 260 B.C. ), marked a turning point in his spiritual development. It makes sense that his edicts would be discovered in Dhauli, in the Mahanadi delta, and at Jaugada, in the Ganjam area, which was undoubtedly a part of Kalinga. Dhauli resembled Tosali, the ancient capital of Kalinga, maybe.

The north-west and north-east of the Deccan were included in the Mauryan empire, according to a remnant of one of Asoka’s edicts that was found at Sopara, close to Bombay. Aokan sculptures have been discovered further south in the counties of Mysore’s Raichur and Chitaldrug as well as Andhra’s Kurnool.

A Pallava stone from the ninth century A.D. (the Velürpälaiyam plates) cites an Aokavarman as one of the early kings of Kanchipuram, though it is unknown how much further south the Maurya empire reached. It also seems doubtful that a part of the Tondaimandalam was associated with it.

In the account provided by the Ceylonese chronicle, Mahdvamsa of such expeditions despatched well after the third Buddhist council at Pataliputra for said transmission of the dhamma in various regions, the lands of the Deccan are very agglomerates.

The Andhras and Paradas of the eastern Deccan, the Rathikas and Bhojas of the western and northern Deccan, as well as the Pitenikas who haven’t yet been localized, appear to have had a sizable amount of autonomy in their governance. They could not have been autonomous because they are unmistakably identified as inhabitants of the king’s domain in Asoka’s inscriptions.

In Andhra Pradesh, along Hampi and Maski, the Deccan region played a significant role in the Mauryan empire and was home to the viceroyalties of Tosali (Dhauli) and Suvarnagiri, now known as Kanakagiri.

Mahdmátras was given control of the territory; some assisted viceroys, some were in charge of areas, and yet others administered justice in the towns. Antamahmtras was tasked with Christian missionaries between backward citizens and defense.

Asokan Inscriptions’ characters in Kurnool and Mysore

The characters used in the Asokan markings in Mysore and Kurnool differ from those used in the northern edicts in a number of ways, and they have been identified as a unique form of Brahmi script used in the south.

This demonstrates that writing had to have been used in the South for a while in order for such variances to evolve, that the southerners comprehended the language, and that they were on par with their North Indian neighbors in terms of culture and worldview.

Asoka’s edicts were likely written not much longer after the writing on the stone relic caskets discovered in the stupa at Bhattiprolu at the Krishna river’s mouth; they are written in the same southern Brähmi script, and their language clearly shows several regional quirks. These inscriptions make reference to King Kubiraka and his father, whose name has been forgotten.

A union of Tamil states that was 113 years old at the time of the inscriptions and had for a while posed a threat to the Kalinga empire is mentioned in the famous Häthigumpha inscription from the first quarter of the 2nd century B.C.

This demonstrates that the various states of the Tamil nation were, even at that young age, capable of developing enduring diplomatic ties and conducting a consistent foreign policy toward nearby and far-off neighbouring governments.

Under the Mauryas, India’s Politics were Unified

The kingdom of Pataliputra was concerned about events in the far south of the peninsula at the time because the Mauryas’ governmental integration of India was a very serious possibility.

The name “Vadugar,” which literally translates as “northerners,” was used in Sangam literature to refer to the Telugu-Kannada forefathers who lived in the Deccan, approximately to the north of the Tamil nation, whose northern border was Vengadam, the Tirupati Hill.

The Deccan was a component of the Mauryan empire, and it is fairly comprehensible to the Mauryan that the Deccani men formed the vanguard force.

Further connections to the Mauryas are made by Mämülanär and other poets that are heavily influenced by the mythology surrounding the idea of Chakravarti, the wheel-emperor, but these should not distract us or lessen the significance of the aforementioned historical references in Mämülanär. Let’s also remark that the poems do not support the commonly held belief that the Mauryas raided South India and made it as far south as the Podiya hills.