The sole early inscriptional statement of the kingdoms of the Tamil nation after the Asoka inscriptions is found in the inscription of Khäravela, which was briefly described in a preceding section.

In the eleventh year of his reign (about 155 B.C. ), Khravela, who ruled over Kalinga in the early half of the second century B.C., is credited with destroying Tramiradelasanghatam, a federation of Tamil states that had been around for 113 decades at the time of Sangam era.

It had long since been a threat. The same inscriptions mention that Kharavela ordered horses, elephants, diamonds, and rubies to be delivered from the Pandya to Kalinga in addition to “many pearls in hundreds.” Even though it is a challenging document by itself, the gaps in the script and its highly worn-out state make its significance severely hazy.

We learn nothing really from any other resource about the Tamil confederacy, its objectives, how it came to be a threat to Kalinga, the steps taken by Khravela to eliminate the threat, and the new connections he made with the Pandyan monarchs.

Probably just a small portion of the considerably larger body of writing from these ancient times has survived. The creation of a Sangam at Madura and the transfer of the Mahabharata into Tamil are two accomplishments of the early Pandyas mentioned in an inscription from the first decade of the first century A.D.

Despite poems written by “Perundevanar has sung the Bharatam” serving as the opening commands for six of the eight collections mentioned above, this transcription has been lost. Sections of a Tamil Bharatam by a Perundevanär have survived to the present day, but the creator was a contemporaneous of Nandivarman III Pallava (9th century AD) and likely unrelated to the Sangam anthology’s namesake.

Flourished Time Under Royal patronage

It may very well be true that a college (Sangam) of Tamil poets functioned for a while at Madura with royal support. However, the earliest description of it, which appears in the discussion on the Iraiyanar Agapporul’s introduction (about A.D. 750), is shrouded in legend.

It speaks of three Sangams that spanned a total of 9,990 years, were attended by 8,598 poets (among them a few Saiva gods), and were supported by 197 Pandyan kings. A number of the names of the kings and poets, such Kadungon and Ugrapperuvaludi, are documented in monuments and other reliable sources, demonstrating how some facts have become muddled with a lot of fiction and cannot be used to draw any meaningful conclusions.

According to a rigorous examination of the elimination wasted between the kings, chieftains, and poets provided by the annotations at the conclusion of the poems, this corpus of literature, or 120–150 years, at most, describes events that occurred over the course of four or five consecutive generations.

We can only create something resembling a continuous history for the Chera line of kings, and this reveals the existence of two lines of kings, each spanning no more than three or four centuries and related by marriage or other means.

In all other cases, we just have random names, which makes it impossible to reconstruct a normal history of the time. Therefore, we must be content with the notable people and their accomplishments that the poets have described.

The Land Of Chola and Pandya

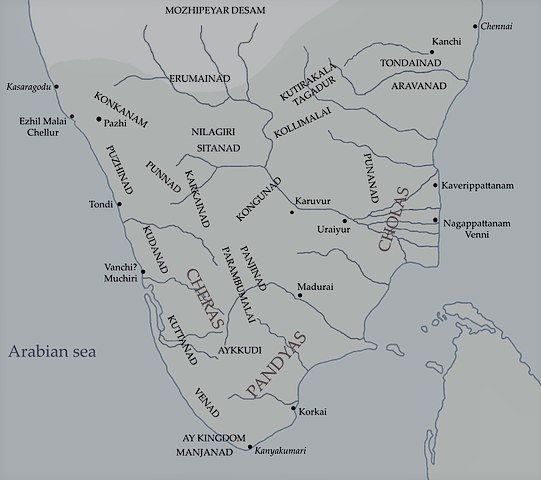

The three crowned kings of the Chera, Chola, and Pandya families shared the kingdom with a number of minor chieftains who, depending on the political climate of the period, either owed allegiance to or actively supported one of these monarchs, or else lived on their own.

Seven of these chieftains were singled out by poets for their liberal support of the arts and literature, and they were referred to as tallals (patrons).

We now know that the Damili inscriptions from the 2nd century B.C. was now used by Jain ascetics and were primarily Tamil with some Prakrit words mixed in. The Tamil language matured in the Sangam period and has started to function as a potent and elegant literary medium.

It has also already absorbed many words and concepts from Sanskrit sources. Additionally, it demonstrates the presence of a complex set of rules that guide how social life is portrayed in literature.

Generations of Chera Rulers

This had to be the end product of a protracted development process that spanned several generations. In-depth information on the publication date of this material has recently come to light. Three generations of Chera rulers—Ko-Adan-cel-Irumporai, his son Perumkadungo, and his son Ilamkadungo—are mentioned in an inscription on the Arnattamalai Hill near Pugalür that dates to the first century of the Christian period. The nicknames Ko Adan and Irumporai make it clear that they are Chera lineage kings.

The Sangam writings contain the poetry of two Chera royal poets: Perumkadungo, who sang of the Palai region, and Ilamkadungo, who sang of the Murdam region.

According to Sangam’s writings, the Perumkadungo and Ilamkadungo of the monument are royal poets of identical names.

Adan-cel-Irumporai, the first monarch of the inscription, was most likely a Kadungo as well and is compared to Selvakkadungo from the Sangam literature.

Further research is required to assess the claim that the three monarchs of the monument are the champions of the Padirrup-pattu collections’ seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries.

The Sangam anthologies are solidly dated to the first two centuries of the Christian era this identification, which is possibly the most significant one for identifying Sangam literature.

The striking similarity between the facts available by the literary works on the trade and other interactions here between Tamil states and indeed the Yavanas (Greeks and Romans) during this time and that of the authors on the subject, notably Strabo, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’s unnamed source, Pliny, and Ptolemy, is another line of reasoning in favour of this proposed chronology for the Sangam age.

Archaeology Discoveries

The data from the literature is supported by archaeology. The numerous Roman gold and silver coin discoveries made in South India during the first 2nd centuries A.D. and the recent discovery of evidence supporting the existence of a “Roman factory” at Arikamedu (also known as Aruhan Medu, a Jaina mound) in the Pondicherry area during the first-century help to support the validity of the techniques are applied for the Sangam era.

Before giving a description of the social life of the time, we can first state the key political facts of the era. The monarchy of the Cheras, Cholas, and Pändyas was thought to have existed since the beginning of time, at least in later times, and the songs of the Sangam speak to their desire to link their histories to that of the Great War between the Kauravas and the Pandavas. According to legend, Udiyan-jeral, the first Chera king we are aware of (about 130 A.D.), lavishly fed both Kurukshetra armies, earning the nickname “Udiyan-jeral of the Great Feeding.”

Nedunjeral Adan, the son of Udiyanjeral, had a naval victory over a local foe on the Malabar coast. He then kidnapped a number of Yavana traders and subjected them to cruel treatment for a period of time for unknown reasons before releasing them after receiving a hefty ransom.

It is reported that he engaged in a number of conflicts and spent a lot of time in camps with his soldiers. He defeated seven crowned kings, rising to the greater position of an adhiraja as a result.

Apparently Extended the Chera Power

In the reign of the Chola ruler, both the monarchs perished, and their queens performed sati. The younger brother of Adan was “Kuttuvan of many elephants,” who overthrew Kongu and reportedly temporarily expanded Chera’s dominance from the western to the eastern sea. Two sons were born to Adan by several queens.

One of them was referred to as “the Chera with the kalangay festoon and the fibre crown”; it’s believed that the crown he wore at his inauguration was composed of palmyra fibre and that the festoon on it included kalangay, a little blackberry.

Although the crown had a golden frame and festoons made of priceless pearls, it wasn’t entirely to be despised. However, it is unclear why the king had to wear such a piece of astonishing jewellery.

Senguttuvan, the Righteous Kuttuva, was the other son of Adan and was honoured in song by Paranar, one of the most well-known and enduring poets of the Sangam era (e. 180).

Legends from a later period, that have no resemblance in the two strictly contemporaneous poems by Parapar—the decad on the monarch in the Ten Tens and a song in the Purandnru—have glorified the life and accomplishments of Sen-guttuvan. They only commemorate a successful war even against chieftain of Möhür as a military accomplishment.

Senguttuvan put a lot of effort into the water, according to Parapar, but he doesn’t go into further detail. He was given the moniker “driver of the sea back,” which is understood to suggest that he rendered the sea useless as a means of defence against his adversaries. If this is the case, he must have kept a fleet.

The only other information we have about him is that, in addition to being a brilliant warrior and a generous patron of the arts, he was an expert rider on horseback and an elephant, was known as adhiraja, and wore a garland of seven crowns.